Boiling point

The boiling point of an element or a substance is the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the environmental pressure surrounding the liquid.[1][2]

A liquid in a vacuum environment has a lower boiling point than when the liquid is at atmospheric pressure. A liquid in a high-pressure environment has a higher boiling point than when the liquid is at atmospheric pressure. In other words, the boiling point of a liquid varies dependent upon the surrounding environmental pressure (which tends to vary with elevation). Different liquids (at a given pressure) boil at different temperatures.

The normal boiling point (also called the atmospheric boiling point or the atmospheric pressure boiling point) of a liquid is the special case in which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the defined atmospheric pressure at sea level, 1 atmosphere.[3][4] At that temperature, the vapor pressure of the liquid becomes sufficient to overcome atmospheric pressure and allow bubbles of vapor to form inside the bulk of the liquid. The standard boiling point is now (as of 1982) defined by IUPAC as the temperature at which boiling occurs under a pressure of 1 bar.[5]

The heat of vaporization is the amount of energy required to convert or vaporize a saturated liquid (i.e., a liquid at its boiling point) into a vapor.

Liquids may change to a vapor at temperatures below their boiling points through the process of evaporation. Evaporation is a surface phenomenon in which molecules located near the liquid's edge, not contained by enough liquid pressure on that side, escape into the surroundings as vapor. On the other hand, boiling is a process in which molecules anywhere in the liquid escape, resulting in the formation of vapor bubbles within the liquid.

Contents |

Saturation temperature and pressure

A saturated liquid contains as much thermal energy as it can without boiling (or conversely a saturated vapor contains as little thermal energy as it can without condensing).

Saturation temperature means boiling point. The saturation temperature is the temperature for a corresponding saturation pressure at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. The liquid can be said to be saturated with thermal energy. Any addition of thermal energy results in a phase transition.

If the pressure in a system remains constant (isobaric), a vapor at saturation temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as thermal energy (heat) is removed. Similarly, a liquid at saturation temperature and pressure will boil into its vapor phase as additional thermal energy is applied.

The boiling point corresponds to the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the surrounding environmental pressure. Thus, the boiling point is dependent on the pressure. Usually, boiling points are published with respect to atmospheric pressure (101.325 kilopascals or 1 atm). At higher elevations, where the atmospheric pressure is much lower, the boiling point is also lower. The boiling point increases with increased pressure up to the critical point, where the gas and liquid properties become identical. The boiling point cannot be increased beyond the critical point. Likewise, the boiling point decreases with decreasing pressure until the triple point is reached. The boiling point cannot be reduced below the triple point.

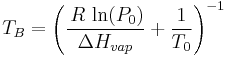

If the heat of vaporization and the vapor pressure of a liquid at a certain temperature is known, the normal boiling point can be calculated by using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation thus:

| where: | |

|

= the normal boiling point, K |

|---|---|

|

= the ideal gas constant, 8.314 J · K−1 · mol−1 |

|

= is the vapor pressure at a given temperature, atm |

|

= the heat of vaporization of the liquid, J/mol |

|

= the given temperature, K |

|

= the natural logarithm to the base e |

Saturation pressure is the pressure for a corresponding saturation temperature at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. Saturation pressure and saturation temperature have a direct relationship: as saturation pressure is increased so is saturation temperature.

If the temperature in a system remains constant (an isothermal system), vapor at saturation pressure and temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as the system pressure is increased. Similarly, a liquid at saturation pressure and temperature will tend to flash into its vapor phase as system pressure is decreased.

The boiling point of water is 100 °C (212 °F) at standard pressure. On top of Mount Everest, at 8,848 m elevation, the pressure is about 260 mbar (26.39 kPa) and the boiling point of water is 69 °C. (156.2 °F). The boiling point decreases 1 °C every 285 m of elevation.

For purists, the normal boiling point of water is 99.97 degrees Celsius at a pressure of 1 atm (i.e., 101.325 kPa). Until 1982 this was also the standard boiling point of water, but the IUPAC now recommends a standard pressure of 1 bar (100 kPa). At this slightly reduced pressure, the standard boiling point of water is 99.61 degrees Celsius.

Relation between the normal boiling point and the vapor pressure of liquids

The higher the vapor pressure of a liquid at a given temperature, the lower the normal boiling point (i.e., the boiling point at atmospheric pressure) of the liquid.

The vapor pressure chart to the right has graphs of the vapor pressures versus temperatures for a variety of liquids.[6] As can be seen in the chart, the liquids with the highest vapor pressures have the lowest normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, propane has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point(-42.1 °C), which is where the vapor pressure curve of propane (the purple line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

Properties of the elements

The element with the lowest boiling point is helium. Both the boiling points of rhenium and tungsten exceed 5000 K at standard pressure; because it is difficult to measure extreme temperatures precisely without bias, both have been cited in the literature as having the higher boiling point.[7]

See also

- Boiling-point elevation

- Critical point (thermodynamics)

- Ebulliometer

- Joback method (Estimation of normal boiling points from molecular structure)

- Subcooling

- Superheating

- Trouton's constant

References

- ^ David.E. Goldberg (1988). 3,000 Solved Problems in Chemistry (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-023684-4. Section 17.43, page 321

- ^ Louis Theodore, R. Ryan Dupont and Kumar Ganesan (Editors) (1999). Pollution Prevention: The Waste Management Approach to the 21st Century. CRC Press. ISBN 1-56670-495-2. Section 27, page 15

- ^ General Chemistry Glossary Purdue University website page

- ^ Kevin R. Reel, R. M. Fikar, P. E. Dumas, Jay M. Templin, and Patricia Van Arnum (2006). AP Chemistry (REA) - The Best Test Prep for the Advanced Placement Exam (9th ed.). Research & Education Association. ISBN 0-7386-0221-3. Section 71, page 224

- ^ Notation for States and Processes, Significance of the Word Standard in Chemical Thermodynamics, and Remarks on Commonly Tabulated Forms of Thermodynamic Functions See page 1274

- ^ Perry, R.H. and Green, D.W. (Editors) (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

- ^ Howard DeVoe (2000). Thermodynamics and Chemistry (1st ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-02-328741-1.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||